practice era is over: an interview with nora nygard

Let's not beat around the bush. Let's get right to it. I've spent the past few months dealing with loss and catastrophe, and it has made me rethink a lot about my life. A friend of mine passed away, and another one had a life-changing medical emergency. And I've been doing a weird thing where I've been grieving and thinking about grief at the same time. Grief and metagrief, feeling and thinking about feeling.

It's like I can't feel the sensation of loss without looking at it from above, remarking on what's happening like I'm a behavioral scientist. You know that Barenaked Ladies lyric, "I'm the kind of guy who laughs at a funeral"? I'm the kind of guy who thinks at a funeral.

Nora Nygard's album I Wish I Could See You arrived in my email inbox at an eerily perfect time. It's an album about grief, and it's also an album about time itself. It's about the death of Nora's older brother Winfred when she was a child, and also about her own long journey back from the brink of total isolation. In her liner notes, which are a candid and beautiful piece of writing on their own, she describes the album as "the culmination of a lot of time spent alone," the endpoint of a five-year period that saw her releasing over 300 pieces of ambient and drone music with little promotional fanfare. At the notes' end, she describes a "spirit visitation" from her brother several months after composing the album.

I Wish I Could See You is a 40-minute composition of flowing Ableton synths, as alive as a river but as calm as a lake. Not long after I pressed play on it, I felt a strong impulse to write about everything that I'd been experiencing lately: not in the behavioral scientist mode, but in more raw, stream-of-consciousness style. Getting angry, getting petty, getting sad. Something in the music unlocked that desire. It was like its particular shape created some space for me to get away from metagrief and toward just plain grief. Even with minimal words—the only lyrics are a spoken poem that slips into the mix in about eight minutes before the album's end—the spirit of the album felt palpable to me.

I emailed Nora back and asked if she'd be down for an interview. The album and liner notes had made a huge impression on me, and I wanted to chat with her more about how they had come to be.

We 'hopped on a zoom,' as they say, and immediately confirmed a mutual love of the iconic underground rock history book Our Band Could Be Your Life before getting into the weeds. Though the concept of grief sort of lurked on the outskirts of our zoom boxes, I didn't want to kick off with quite that level of heaviness.

Instead I started the conversation by asking about the effect of isolation on Nora's music. Her liner notes describe her years making ambient music as extremely secluded, a total closure of collaboration that she initiated after years of making music with other people in punk and emo bands. Nora composed I Wish I Could See You over a few weeks in spring 2020, a time when everyone was getting a gnarly taste of solitude, though her notes make a point to distance her music from explicit "lockdown project[s]" because she "was hesitant to add anything trite or predictable to the endless flood of music being published."

Molly: How do you feel about the concept of 'the Covid project'?

Nora: I was one of these freaks who...it changed a lot in my life, obviously, but I'm used to being alone all the time. So it was like, Welcome to my world, everybody. I don't actually have anything against any of that shit, but why was everyone calling their memoir "something, something, Plague Years"?

Molly: I do feel like the meme-ification of Covid was a collective response of everyone wanting to downplay it, to not be so scared of it, but also to codify it. Like, once everyone started using nicknames for the pandemic, calling it "the Panera"? People were trying to have this collective language for it, and it didn't feel quite right.

Nora: Especially with music industry stuff, a lot of it seemed to be: this was the marketing trope that was working. You know, taking a crisis and turning it into an opportunity is a great way to make money, and I think there's something incredibly cynical about that. I was very resistant to having a 'Covid project.'

When I brought up the isolation preceding this release, she talked about how difficult it was for her to release music at all. "I've been resistant to releasing things, because it's like, who gives a fuck? In my late teens, early twenties, my ambition quickly turned into, Wait, I'm just fuckin' bad at all of this. And I might as well try to get good at it. I think that's an endless road that you can take. And I don't think it's what people want. People don't actually want good music. People want the personal connection."

"Wait, I'm just fuckin' bad at all of this. And I might as well try to get good at it."

I expressed surprise at this last opinion, and Nora invoked the ultra-DIY, Our Band Could Be Your Life-featured band Beat Happening: "Some of the worst vocals in rock and roll, but some of the best vocals in rock and roll. It's the 'so bad, it's good' thing. Now you look at Drain Gang, Bladee, and one of the tropes there is people saying, 'Yeah, it sucks, but you get used to it.' I've always liked music that's a little bit stupid. Like, one of my all-time favorite bands is They Might Be Giants. So stupid, but the best band. People don't like 'good'."

Definitely true in many cases. But this Nora Nygard album feels, in its reflective glow, far beyond the concept of "good" or "bad"; it's definitely not "stupid," and yet it has forged social connection all the same. Remembering the fantastic sound of the album as if getting bonked by a cartoon mallet, I asked Nora to explain the technical creation of I Wish I Could See You in terms "a slight idiot" (me) could understand.

"I was trying to break my computer," she said. She used some back-end Ableton features, like LFO—"it allows you to take a parameter and change it slowly over time"—to incrementally manipulate droning sounds, stretching her MacBook to its breaking point in the process. "I lost a lot of project files, because I couldn't reopen them. So I would set one up, export the audio and then re-edit that audio," she said. "The nice thing about that is you lose control over it. You're not able to be a perfectionist because everything is breaking."

You're not able to be a perfectionist because everything is breaking. If that doesn't sound like grief, I don't know what does. Grief cracks control freaks like Barry Bonds cracks homers. I told Nora how the album inspired me to write about my own experiences with grief, and then we started talking about her brother Winfred—Win for short.

In the liner notes, Nora describes Win as a studious brother who tried to teach her algebra, and encouraged their parents to get Nora a Game Boy to play Pokémon Blue on. In our conversation, Nora described Win as "an early case of 'extremely online.'" He spent "all day, every day" on the primeval internet messenger I.R.C., and built an online fanbase as a teenager by publishing a regular webcomic. "Just classic 2000s nerd shit," Nora said, smiling. "It's so goofy, but also it makes me love him so much."

She noted a tension, in wanting to talk about Win, between privacy and publicity. "There are these different things pulling me. One is a protective feeling. The other aspect is: I want to share his story. Because I think Win's story is incredibly valuable. He was this eccentric, gay, extremely bullied kid from North Dakota. I want to be able to tell people about his life, without giving all of it away."

Win died of chronic illness that Nora suspects was exacerbated by alcohol use; last year, "brutally depressed," Nora felt moved to revisit his webcomic and discovered a daily blog he published alongside it, which she read in its entirety: "Reading that much shit from him wrecked me. And the worst part of it was getting to the end of it." The blog's paper trail wasn't the only digital snare she encountered in the wake of Win's death. She referenced "pretty insane cyberbullying" that happened before he died, as well as some upsetting incidents that happened afterward: someone impersonating Win online, someone else who had mocked his webcomic reappearing in a new form. Dying in the age of personal computing has invented so many new and painful ways of experiencing loss. I thought about the Ableton files breaking under the stress of stretching time.

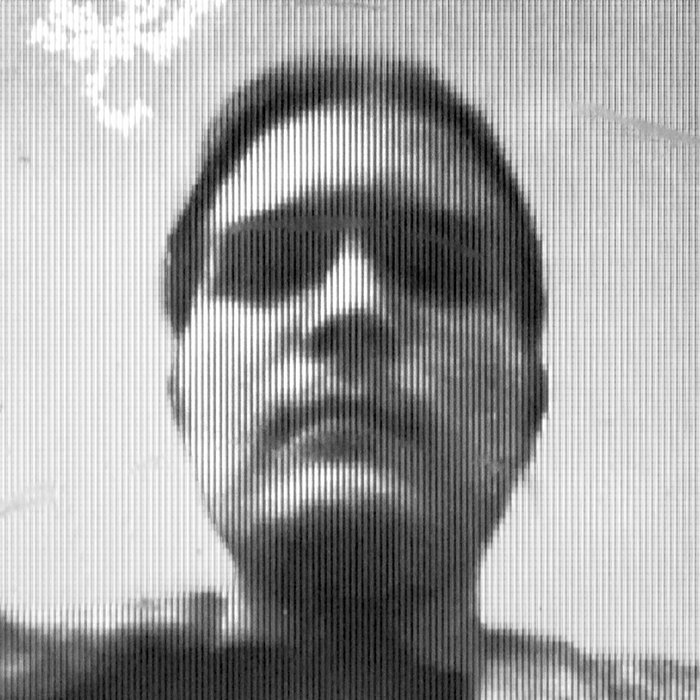

The album art for I Wish I Could See You even fits within this thematic zone. It's a photo of Win taken on his mid-'00s flip phone—"one of the only selfies he ever took"—so technologically ancient that it couldn't be exported as a digital file. The album art is a photo of the photo displayed on the cell phone itself. Another facet of grief: the world moves forward, even if the person you love doesn't.

The phone holds "so much emotional resonance" for Nora. "In some ways it's a memory of him, but it's also this memory of me not being able to—and not being helped to—process my grief as a child," she said. "I've lost so many memories of Win. And the memories that I do have, I want to hold very close. Even sharing this photo, I feel the memory around this photo and this phone changing, and that is so bizarre."

Her voice was calm and steady. "This feels incredibly embarrassing to say, but in the last month, thinking about all of this, writing about all of this and putting this [album] out, I had this realization: he's my muse. So much of my writing is either about him directly or about this traumatic childhood experience of losing him, and the way it affected me in ways that I still barely understand. I see that in everything now. It feels so weird to be like, 'Yeah, my dead brother's my muse.' But that's just the way it's shaken out."

"Writing about all of this and putting this [album] out, I had this realization: he's my muse."

I felt the fullness of the responsibility, right then, of needing to get Nora's story, and Win's story, right. It felt a little impossible in that moment to think about filtering such a vulnerable and artistic expression of grief through blogging. Music writing is so funny. There's an easy and lazy way to do it, which involves flattening everything into a nice foldable shape, turning bands into paper dolls. Codifying genres, calcifying narratives, fortifying clichés. The harder way, the way I'm trying to do it, is to try to let everything live in the same shape it came in. And this album and this conversation was grief-shaped: a Möbius strip, maybe, or an Escher lithograph. Climbing the stairs over and over.

We ended our conversation by talking about the future. Nora has affirmed that I Wish I Could See You marks an end to her isolation, and moving forward, she will focus on more collaborative mediums for her music.

Molly: Does this album really feel like a bracket, in a sense, on a certain way of creating?

Nora: Definitely. My main focus, especially this year, is starting to compose for contemporary dance. It's so much fun. It's a totally different mindset for making music. And then I just want to start playing shows again. That's how I came up, you know? Honestly the only part of any of this that I feel like I have any talent at is going psycho on stage. I want to leave cerebral music behind. Friendship ended with cerebral music. Music in my body? New best friend.

Molly: [giggling]

Nora: And I wanted to shout out two things that I have coming up, that are probably a 2025 thing. First thing, working title: The Night Walker. In 2021, I had a weird type of mental breakdown where for ten days straight, I improvised 496 songs. I've cut these down to about 170. It's three and a half hours long. People are going to hate it, but I'm pretty excited about it. Second thing, working title that I've had since I was a child: What to Do About Everything You Can't Fix. It's a demo album, 10 hours, 34 minutes, 419 tracks.

Molly: WOW.

Nora: I have so much unfinished music and I feel like I've never going to finish it, But I want to just have it be out in the world. And I'm really, really looking forward to playing shows. I just want to make artsy-ass party music that gives people a reason to dance and get drunk. Extremely emotional party music. I want to get back on my New Order shit.

After saying our Zoom goodbyes, I tried to synthesize—pun not intended, jk, unless—everything that I'd gathered from our conversation. Nora Nygard broke her computer making an ambient album about grief, and now she was going to make party music. She spent years alone, making music and occasionally going mad, and now she was putting music definitively out there, putting herself out there. Never has the concept of an album release felt so accurate. A short sentence from her liner notes still stands out to me: "Practice era is over." It's how she feels about bringing her solitude to a close, and also, weirdly, how I feel about my life after all the destabilization of the past few months. Practice era is over. It sucks, and it's amazing.

Thank you Nora ♡ I highly recommend listening to I Wish I Could See You. Nora also has an incredible podcast called Prairie Goth and you can support her on Patreon. And thaaank you for reading I Enjoy Music. If you like the blog, tell a friend about it.